Bringing it all back home

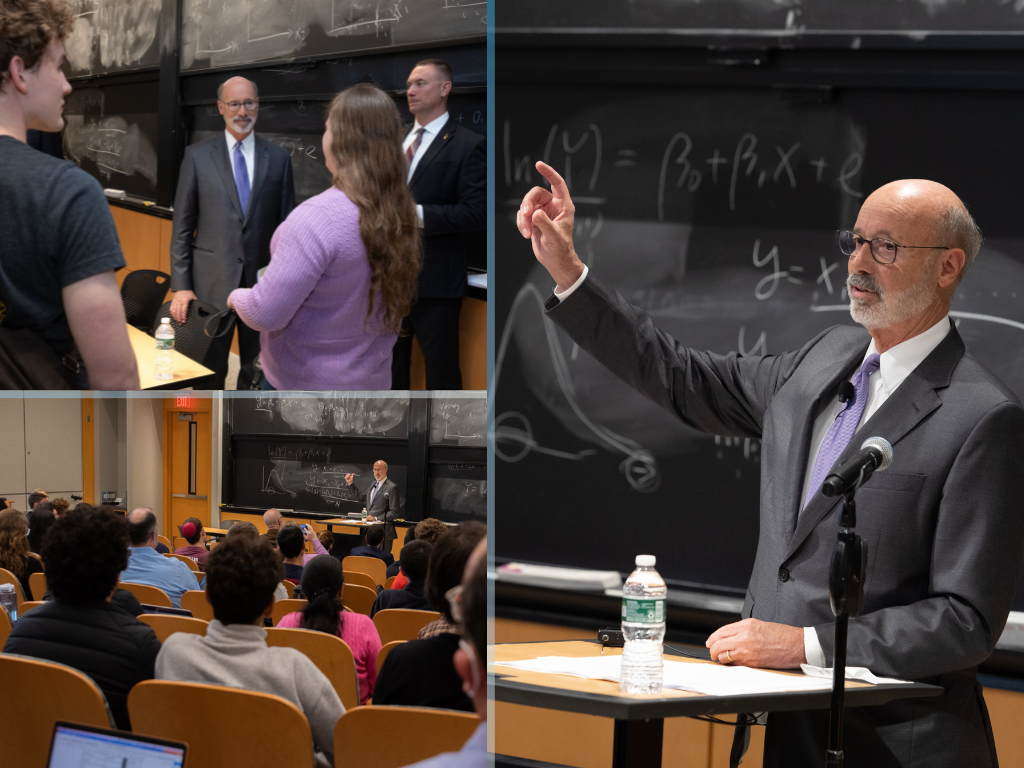

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf PhD ’81 made a robust call for reviving American manufacturing while speaking at MIT on Thursday, contending that if U.S. states pursue broad, long-term measures to improve the business climate, quality of life, and social safety net, they will also spur more manufacturing investment.

“It’s a challenge to reinvent ourselves as a healthier, stronger, more equitable and just society,” said Wolf, who received his doctorate in political science at MIT.

Manufacturing employment in the U.S. peaked at around 20 million workers in 1979, then crashed to a low of about 11.5 million in 2010. The country has added a million manufacturing jobs since then. Elected officials and policymakers thus have recent successes to point to, although, as Wolf acknowledged, adding more manufacturing jobs is possible but not a certainty.

“I think it’s a legitimate question,” said Wolf, who is concluding his second and final term as Pennsylvania’s governor. “Can we do it?”

Wolf’s career has brought him multiple ways of thinking about the topic. After graduating from MIT, Wolf did not enter academia but moved back to his family’s home area near York, Pennsylvania, where he managed a family-owned hardware store and entered the family’s lumber business. Eventually the business, Wolf Home Products, became both a distributor of building supplies and a firm selling its own branded lines of cabinets, sourced and built in the U.S.

Wolf served as Pennsylvania’s secretary of revenue in 2007-2008, was first elected governor in 2014, and was re-elected in 2018 by a 17-point margin.

In his talk, which was the first in a new Manufacturing@MIT distinguished speaker series, Wolf focused on two main questions about creating more manufacturing — Why should we care? And can we do it? — followed by an outline of the policy approach he has used in his own state.

To address why we should care, Wolf drew from the 2013 book “Making in America,” written by MIT political scientist Suzanne Berger following the work of MIT’s Production in the Innovation Economy (PIE) task force. Berger, an expert in manufacturing policy and MIT’s inaugural John M. Deutch Institute Professor, was in attendance on Thursday.

As Wolf observed, having substantial domestic manufacturing in the U.S. allows people to have generally well-paying jobs; serves the country’s strategic interest, by ensuring that key products are available; means the U.S. keeps intact its capacity to train many high-skill workers; and maintains a culture of innovation that links universities, research labs, and producers of goods.

“Connecting the plant floor and the laboratory is actually very important,” said Wolf, noting that many successful products do not emerge full-blown from the lab but are improved in the process of being produced. Concerning America’s strategic interests, Wolf noted that the pandemic showed how hard it was for the U.S. to obtain basic medical supplies — “We were at the mercy of foreign producers” — and said he supported the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which bolsters semiconductor manufacturing and science funding.

As to whether it is possible for more U.S. manufacturers to beat foreign competitiors, Wolf point to his own experience with Wolf Home Products.

“I spent 25 years in business where we did go head-to-head with overseas business, and we won,” Wolf said.

Wolf’s policy prescription for encouraging manufacturing is by his own account somewhat idiosyncratic, focused on sweeping measures to create a good business and civic environment, which may both appeal to manufacturers and provide societal benefits.

“It’s not I think what the conventional wisdom is,” Wolf said. “Public policy for economic development for manufacturing, or any other form of economic development, [is an area where] really good policies ought to be broad, and they’re only there to set the table.”

By contrast, Wolf said, too many locales spend too much taxpayer money developing offers for specific manufactures to relocate or expand, but end up signing mediocre deals.

“By the time they’ve finished, they’ve basically negotiated away any social utility that might have come from getting that manufacturer to come to your place,” Wolf said.

Instead, Wolf favors other long-term policies. He oversaw a reduction of his state’s corporate income tax, to “send a signal” that Pennsylvania was “open for business.” The state has also invested in human capital, including research programs and education on multiple levels. Wolf supports a variety of quality-of-life measures that make places more appealing to live and work, even citing his own record of creating new state parks.

Wolf also noted that there should be universal health care, to prevent the scenario in which people stay in jobs only to retain their existing insurance.

“Otherwise, we suffer from ‘job lock,’” Wolf said, recounting a forklift operator at the family business who said he wanted to be making furniture himself but was staying with Wolf Home Products only because of the benefits.

On multiple occasions, Wolf praised the flexible structure of American public education, which gives students the chance to change their minds about their areas of study and careers for much longer than in most other countries. It is, he said, “a system that basically allows you, encourages you, to be creative. We can make it better. I get that. But we start with a pretty good basic model that’s unique in the world.” Still, he noted, the U.S. can do better at “life-long learning,” giving workers the opportunity to change careers later in life, too.

Wolf also noted that under his watch, Pennsylvania had put more funding toward support of universities’ research capacities, development of renewable energy, and improvements in ports, in Erie, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia, all of which can increase the state’s manufacturing capacity over time.

He also added that business should take diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts seriously, to make sure they are not excluding talented workers.

“Here’s the truth,” Wolf said. “If you’re a business and you’re not [going forward] with that, you’re cheating youself.” He added: “It’s not just morally right, but it’s also the smart thing to do.”

At the event, Wolf was introduced by MIT Provost Cynthia Barnhart and by Richard Samuels, the Ford International Professor of Political Science and director of MIT’s Center for International Studies.

“He put in place policies and programs to support Pennsylvania’s transition from steel, coal, and mining, industries that had declined sharply over the past 50 years,” said Barnhart. “His administration successfully worked with industry, academia, and NGOs to attract new manufacturing businesses and private investment, spurred job growth, and trained a pipeline of workers with skills in advanced manufacturing.”

Samuels has known Wolf since the two were in the same entering PhD class in political science at MIT. Samuels observed that Wolf’s “commitment to public service is anchored in southeastern Pennsylvania,” praised Wolf’s attitude toward employees — the family firm has used a profit-sharing system to supplement incomes — and cited Wolf’s “integrity” as one of his core characteristics.

For his part, Wolf also noted that “MIT was a really special place” for him, adding, “MIT’s the place that I think really was where I left my heart. And I think it’s the collaborative culture … that really makes this place special.”