Hacking apparel becomes lucrative business for alumni

Gihan Amarasiriwardena ’11 has always been a hacker, but not the traditional kind: He hacks clothing and outdoor gear. Since adolescence, he’s cobbled together custom waterproof jackets, heat-trapping sleeping bags, and performance dress shirts.

In 2012, that hobby led Amarasiriwardena to co-found, with other MIT clothing tinkerers, Ministry of Supply, a Boston-based innovator of high-tech fashion. The company has developed a rapidly growing science-based clothing line and the industry’s first 3-D robotic knitting machine.

“The mission and vision of this company is inventing apparel. It’s very MIT in that regard. Instead of hacking code, we’re hacking fibers,” says Amarasiriwardena, who co-founded Ministry of Supply with MIT Sloan School of Management alumni Aman Advani MBA ’13 and Kit Hickey MBA ’13, and mechanical engineering alumnus Kevin Rustagi ’11.

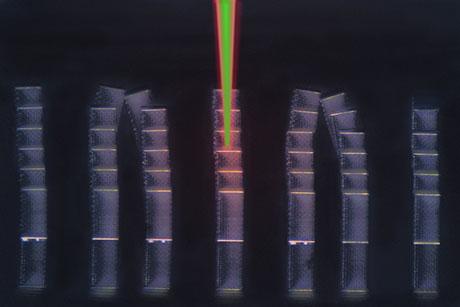

Having last year expanded nationwide, both online and to nine retail locations, Ministry sells about 100,000 products annually, ranging from aerospace-tech dress shirts to socks that use coffee grounds to mitigate odor. In April, the startup launched the fashion industry’s first machine designed to 3-D-knit personalized blazers on demand.

Customers can plug blazer customizations — such as size, and yarn, button, and cuff color — into a computer at the machine, a 10-foot-long printer set up near the checkout counter of Ministry’s Newbury Street headquarters. An image appears on an interactive display, and modifications can be made on the fly. Inside the machine, four beds with 4,000 needles each pull yarn to knit the garment. In about 90 minutes, the machine spits out a blazer that stays at the store a couple days for finishing touches such as steaming and shrinking. According to the startup, the machine eliminates about 30 percent of the fabric waste of traditional cut-and-sew methods.

Ministry of Supply collaborated with the manufacturer, Shima Seiki, to “hack” the machine to make blazers, by using thermoset yarn that shrinks to size, among other innovations. The first 3-D-knitted garments sold out in a day, and the machine has since become popular with customers. But, Amarasiriwardena says, the machine is important for another reason: “It’s a testament to our technology roots.”

Creating the first “Franken-shirt”

As a boy scout and frequent camper in high school, Amarasiriwardena sought to make better outdoor clothing and gear. To make a waterproof jacket, for instance, he laminated fleece onto flimsy trash bags. Soon, he graduated to sticking ripstop — material used for rain jackets — onto a more breathable housewrap material he grabbed from construction sites. He’d also run Mylar, a material used for thermal blankets, through his parents’ paper shredder and stuff the strips into the lining of his sleeping bag so it would reflect any heat back to his body.

“It was these small hacks that made me think I would someday start an outdoor gear company or performance material company,” Amarasiriwardena says.

But when he started studying chemistry and biological engineering at MIT, and was biking daily, he experienced a major problem: There were no performance dress clothes. “The performance gear I wore wicked away moisture, and kept you cool and dry, but didn’t cut it when it came to looking sharp. I realized there’s a big opportunity to take technology to clothing that we wear for 12 hours a day, when we’re not at the gym or on the mountain,” he says.

Supported by MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) and Sports Technology Education at MIT (STE@M), Amarasiriwardena spent two summers at the Sports Technology Institute at Loughborough University in England, where he and other researchers conducted clothing stress-strain analyses. Sticking sensors on test subjects’ chest, back, and dress shirt, they tracked how the skin and material stretch. They noted lateral stretching at the top of a person’s back where, on traditional dress shirts, there’s a straight, inflexible seam. “You can imagine someone hunching over bike, while biking to work, and the material not stretching,” Amarasiriwardena says.

Back at his Phi Kappa Theta fraternity chapter room, Amarasiriwardena cut up running shirts and sewed them into wrinkle-free dress shirts. On the back, he added a stretchy, curved polyester panel that allowed for stretching. To the underarms, he sewed patches of odor-control material made of silver-based antimicrobial fabric. “It looked like a ‘Franken-shirt,’ but it did the job,” Amarasiriwardena says, laughing.

With Rustagi, a friend and mechanical engineering student, Amarasiriwardena began selling the shirts around campus, while taking 15.3901 (New Enterprises).

Launching Apollo

In the fall of 2011, the duo set up shop in the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship to make performance dress clothes. In a remarkable coincidence, they met a separate team that included Hickey and Advani, a trained industrial engineer with a similar hobby: He had cut off the bottoms of his dress socks and sewn on material from moisture-wicking running socks. Hickey and Advani’s team was making performance underwear, socks, and undershirts for professionals. “That’s the beauty of the Entrepreneurship Center, which is kind of this intersection of engineering, design, and marketing and business coming together,” Amarasiriwardena says.

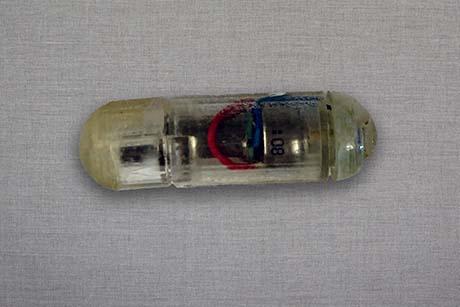

At the time, early team member Eddie Obropta ’13, SM ’16, was working in MIT’s Man Vehicle Laboratory on spacesuits for astronauts traveling to Mars. The materials in the suits basically melt and freeze based on skin temperature by absorbing any excess heat from the body, so they could withstand extreme temperature swings on the Red Planet.

After coming together to form Ministry of Supply — named after the defunct department of the U.K. government responsible for designing and supplying equipment to the British armed forces — the team used similar temperature-regulating materials to invent the Apollo dress shirt for professionals.

“Riding the T in the summer in Boston, it could be 95 degrees. As your body temperature starts to elevate, the material will melt around your skin temperature, storing that heat in the shirt. When you get into an air-conditioned office, it freezes and releases that heat back to you,” Amarasiriwardena explains.

After selling about 700 of the shirts around Boston, gathering feedback from wearers, and developing a refined prototype, the startup launched a Kickstarter campaign in 2012, with a goal of $30,000. They raised $430,000, making this the most-funded fashion project on the site.

Engineering fashion

Since then, Ministry has opened nine stores across the country and developed a growing clothing line of pants, shirts, socks, and sweaters for men and women, made with the temperature-control technology, form-fitting material based on NASA spacesuits, and stretchable materials derived from Amarasiriwardena’s early experiments. A notable innovation was a line of socks with spent coffee grounds — residue obtained during the brewing process — mixed into the yarn for odor control.

“With spent coffee grounds, you dilute the coffee flavor and aroma, and you’re left with organic sponge that will trap any aromatic compounds, or odor molecules, and absorb them into fabric,” Amarasiriwardena says. In 2013, the startup launched a Kickstarter just for the socks, seeking $30,000 and raising more than $200,000.

Key to the startup’s success, Amarasiriwardena says, has been its scientific iterating process. For each new garment, the startup researches, designs a prototype for customers to test, and gathers client feedback on moisture management, flexibility, new dyes, and knit structures, among other features. “It’s a process fundamental to engineering, but one that’s absent in traditional apparel design, where you don’t see a design until it hits the runway. That’s often times why fashion has focused on style changes but not making apparel better,” Amarasiriwardena says.

As for the new 3-D knitting machine, Amarasiriwardena says it isn’t just a gimmick — it’s the future of fashion. Right now, the machine can only make blazers, but the startup plans to tweak it to produce other garments. Taking up such a large part of the store, Amarasiriwardena adds, the machine is also a great educational tool, where customers can see how their clothing is made and learn about the 3-D-knitting process. “Technology shouldn’t be something that you are afraid of and have to hide away,” he says. “It can actually be a key part of the retail experience.”