Making 3-D printing as simple as printing on paper

If you haven’t used a 3-D printer yet, you may be surprised to learn that it isn’t fully automated the way your office’s inkjet is.

With paper printers, users queue documents from a computer, and each finished sheet drops neatly into a tray, waiting to be collected. With commercial 3-D printers, however, designs are manually programmed into the printer, and each finished part is manually removed before starting a new print, which is very time-consuming. At schools and businesses, a trained expert usually handles all prints, which can be expensive.

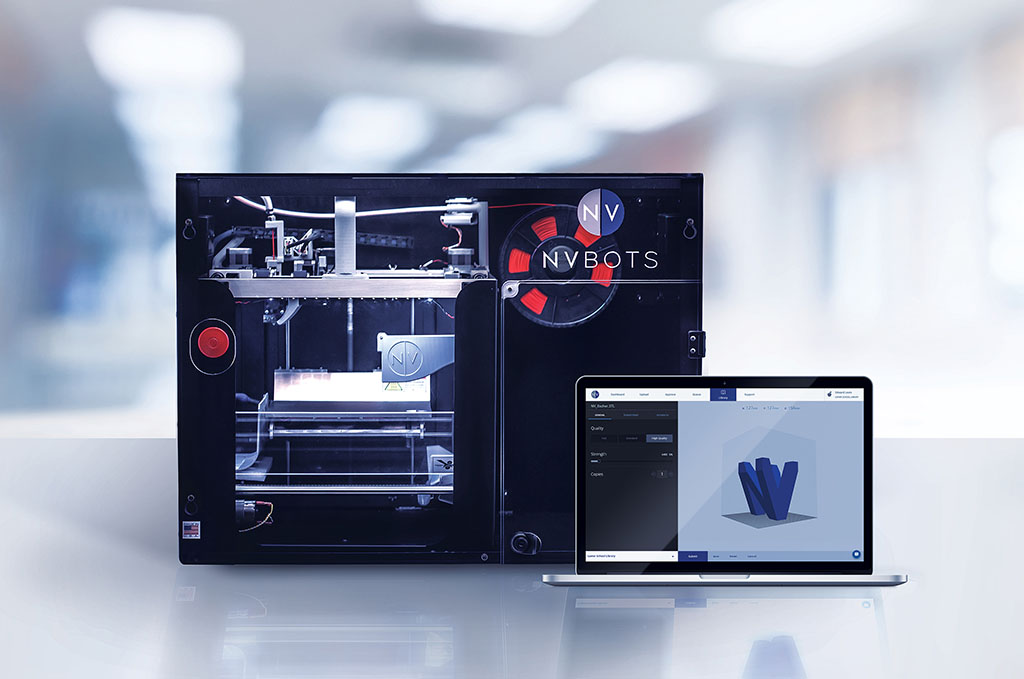

Now MIT spinout New Valence Robotics (NVBOTS) has brought to market the only fully automated commercial 3-D printer that’s equipped with cloud-based queuing and automatic part removal, making print jobs quicker and easier for multiple users, and dropping the cost per part.

To use the printer, called NVPro, a user submits a project from any device, which queues up in the NVCloud software. When a part gets printed, a retractable blade cuts the piece out and moves it into a bin, and the next project begins automatically. Projects can be monitored remotely via webcam.

Invented several years ago in a MIT fraternity house’s basement and commercially launched last April, the printer is now used at more than 100 businesses and schools, primarily as an education tool. Over the past year, there have been more than 84,000 prints, saving more than 165,000 labor hours, according to the startup.

NVLabs, the startup’s research arm, is now bolstering security, analyzing big data, working with materials, and improving human-robotic interfaces for 3-D printing. In January, NVLabs spun out Digital Alloys, a startup developing high-speed, multimetal manufacturing systems that run at lower costs than traditional systems.

The company envisions a world in which 3-D printing is as easy and commonplace as printing on paper — and perhaps more globally accessible, says chair and co-founder Alfonso (A.J.) Perez ’13, MEng ’14. “Our mission is to allow printing with any material, at any time, and from anywhere in the world. This means you could be on a beach in Bora Bora and control a machine at MIT with the click of one button,” he says.

The other co-founders are Chris Haid ’14, general manager at NVBOTS; Forrest Pieper ’14, director of software at Digital Alloys; and Mateo Peña Doll, director of hardware engineering at Digital Alloys.

From the basement to NVBOTS

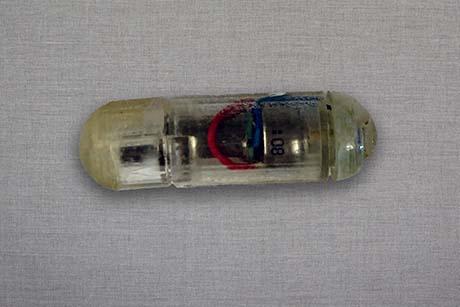

As undergraduates, the four NVBOTS co-founders were brothers of Phi Delta Theta and dedicated “makers.” Outside the classroom, they worked on various projects that involved 3-D printing parts, such as medical devices and a number of other gadgets. But whenever they wanted a part, they’d submit a computer-aided design (CAD) file to a 3-D printer location on campus and wait for the product, which took days.

To expedite production, the group built a custom 3-D printer in the fraternity house’s basement. It was exciting at first, but everyone in the house soon wanted to print at the same time. The solution was a cloud-based queue and webcam to monitor the printer which, at the time, was the first of its kind, Perez says.

But each part still needed to be manually removed. “If it was 3:00 in the morning, and you wanted to start the next job, you had to get up and go down into the basement and start it,” Perez says. “That was an untenable solution for us lazy students.”

To rectify that issue, the students created an automated part-ejection mechanism. After a part has been printed, the print plate is lowered. A blade moves over to the plate, wedging underneath the part. As it moves across the plate, the blade cuts away the part and pushes it into a bin. The blade retracts and the plate rises back up.

Being new to the technology, Perez was shocked that, despite decades of operation, 3-D printers couldn’t automatically eject parts. The four students filed patents with the MIT Technology Licensing Office but didn’t plan on becoming entrepreneurs. That changed after they brought to the 2013 MIT Tech Fair “a quintessential MIT prototype — a rat’s nest of wires,” Perez says.

Numerous 3-D-printing experts asked the students where to buy the automatic part-remover. Moreover, novices didn’t realize the technology and the queuing software were new. “When the early adopters — the experts — are saying that this is the solution to a problem, and the general population already expects the solution to exist, that was the ‘ah-ha’ moment,” Perez says.

That summer, “things got serious,” Perez says, when the co-founders entered the Global Founders Skills Accelerator (now MIT delta v), held in the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship. There, they fleshed out a business plan and learned about profit margins, earning customers, and company ownership, and they officially incorporated NVBOTS.

For 6-year-olds and PhDs

NVBOTS initially designed printers for education. The idea is to develop curricula that uses 3-D-printed models as teaching aids for any subject — such as printing Roman figures for history lessons, Egyptian art, or a human heart for an anatomy class.

“If you want to teach the physics of projectile motion, you can use our catapult lesson that teaches about the math by flinging balls across the room,” Perez says. That type of hands-on learning, he adds, helps “tickle those emotions that MIT shoots for — ‘mens et manus,’ mind and hand.”

Pilot programs began in 2014 at Newton North High School and the Sizer School in Fitchburg; the printers are now in dozens of schools in the region and beyond. Printers are usually put in a central area for all to use. Every student can sign up for an account to submit parts for printing, but only one administrator approves or rejects the parts. MIT Copytech is currently piloting a printing service with the NVPro.

The machines require minimal training and oversight, which is a benefit for schools, Perez says. “Teachers like to teach. Teachers don’t like to maintain a machine, and schools can’t afford to pay for someone to run a machine,” he says. “On a basic level, we wanted to create a 3-D printer that’s so easy a 6-year-old could use it, but a PhD could use it as well.”

In fact, Perez notes, the printer only has one button: “the giant emergency stop button.”

Over the past year, the startup has also sold to companies in automotive, construction, medical devices, consumer goods, aerospace, and architecture fields. Usually it takes days or weeks to 3-D print, say, a building model or a medical device part. With NVBOTS, clients can upload a design on the cloud and pick up the product themselves within a day, with no need of a trained expert. The reduced cost of ownership and the labor saved significantly lowers the price per part compared to traditional 3-D printers, Perez says.

This also gives more workers the ability to find solutions for engineering and other company issues, Perez says: “Everyone who signs up for an account can become a problem solver.”

Making metals, improving printers

Moving forward, NVLabs and Digital Alloys will bring even more innovations to 3-D printing, Perez says.

Digital Alloys is developing a new print head that, according to the startup, allows for multimetal prints at significantly higher speeds than traditional methods, for aerospace, defense, and automotive applications.

Traditionally, metal printing systems are a layer-by-layer slog. One layer of powder, about 20 to 50 microns thick, gets spread across a plate. A laser positioned above the plate melts one layer of powder to the layer below. This repeats until the object is complete. Digital Alloys’ process uses thicker wire as the material, which builds up more quickly. The industry leader for metal printing produces 2 kilograms per day, while Digital Alloys produces 20 kilograms, Perez says.

NVLabs is gathering data on NVBOTS printers to improve performance. Each time a user prints, the startup gathers data on the job’s success, quality, length, and material, among other information. Since launch, the startup has generated 3.8 terabytes of data related to the manufacturing process. The lab is also tackling security issues, improving human-machine interfaces, and, as a major challenge, enabling 3-D printing with any plastic.

“There’s a crazy world of polymers that can be used for printing,” Perez says. “That’s a big aspect of what we’re working on.”