Whitehead Institute receives $10 million to study sex chromosomes’ impact on women’s health

Gift establishes the Brit Jepson d’Arbeloff Center on Women's Health.

The Whitehead Institute has announced that Brit Jepson d’Arbeloff SM '61 — a pioneering engineer, advocate for women in science, and philanthropic leader — has made a $10 million gift to support research uncovering the biological consequences of the sex chromosomes on women's health and disease. The gift, one of the largest contributions ever made to the Whitehead Institute, will underwrite the establishment of the Brit Jepson d’Arbeloff Center on Women's Health within the institute’s Sex Differences in Health and Disease Initiative.

The overall initiative is a comprehensive effort to understand sex differences at the molecular level — a long-neglected area of biomedical research — by building a fundamental understanding of how the female and male genome, transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and metabolome differ. In the long run, determining the practical implications of those differences should lead to better, more effective treatments for both women and men.

The initiative holds particular promise for understanding health and treating disease in women. The d’Arbeloff Center is designed to drive progress toward that promise: catalyzing basic and translational research studies and collaborations that transform health care for women.

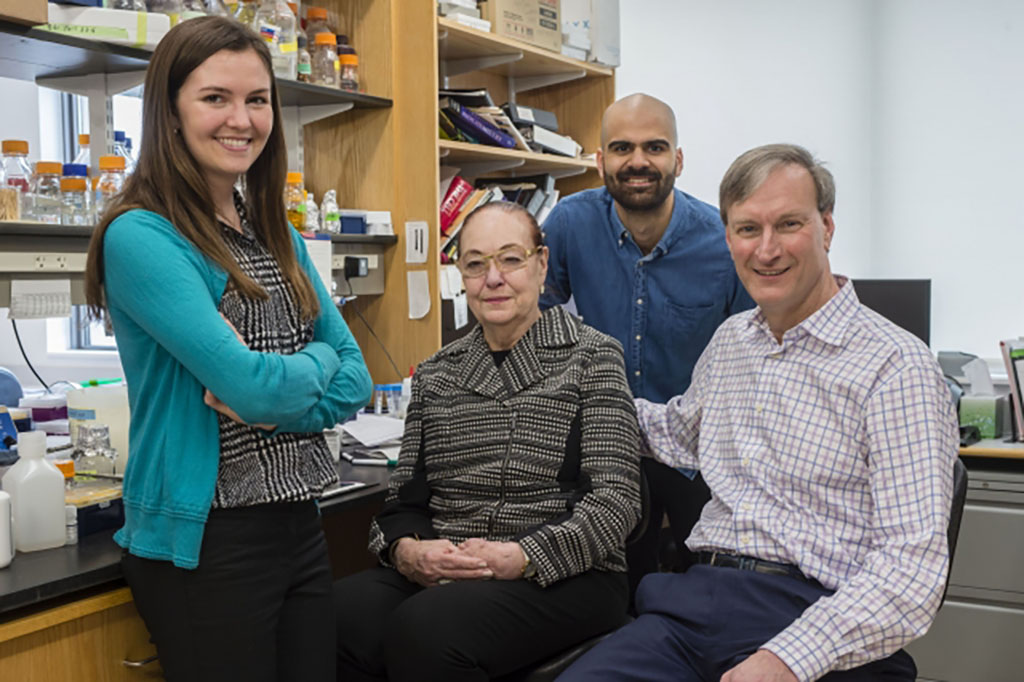

“Brit d’Arbeloff has been a trailblazer in science, research, and education,” says David C. Page, Whitehead Institute director and MIT professor of biology, who leads the sex differences initiative. “This is just the latest example of her determination to help drive biomedical research forward in significant ways. She is a staunch supporter of our work to understand the effects of the sex chromosomes on human health and disease, and her leadership and generosity have enabled us to build a solid research foundation.

“With this extraordinary new gift, she empowers us to build on that base by pursuing and translating discoveries that address the gaps in knowledge about health and disease in women,” Page says.

D’Arbeloff, a member of the Whitehead Institute’s board of directors since 2008, says, “I have long marveled at the stream of scientific discoveries and technical advances by Whitehead Institute researchers. For me, the most exciting of that work is being done within the sex differences initiative — exciting for both the imperative task it is taking on and the invaluable knowledge it is creating. The initiative will help to redress the longstanding inadequacy of research into women’s health and disease, and to catalyze development of therapeutics that are demonstrated effective for women.

“I believe that this is an essential biomedical quest, one as challenging today as the Human Genome Project was in 1991,” d’Arbeloff says. “No institution is better positioned to lead it than Whitehead Institute. And, in creating the Center for Women’s Health, I cannot make a more important investment in the health of my grandchildren and their children.”

D’Arbeloff is known for her enduring commitment to advancing biomedical research and to ensuring opportunities for women scientists and engineers. It is a commitment born of her own experience. She was the first woman to earn a mechanical engineering degree from Stanford University, graduating at the top of her class, but she had difficulty finding a job. When she earned a master’s degree at MIT in 1961, she was the sole woman in the school’s mechanical engineering department. She went on to become part of pioneering industries — contributing to the design of the Redstone missile in the 1960s, then programming software for Digital Equipment Corporation and Teradyne. For decades since, she has supported the efforts of women to succeed in science and engineering by offering her energy and leadership, her knowledge and experience, and her philanthropy.

While d’Arbeloff has provided substantial philanthropic support to a range of nonprofit organizations, she has had a particular impact in education, science, and technology. For example, beyond her decades of support for the Whitehead Institute, she established an MIT-based summer program to introduce female high school students to engineering careers, founded the Women in Science Committee of the Museum of Science, Boston, and supported the MGH Research Scholars Program to advance the careers of emerging clinical researchers.

The d’Arbeloff Center will create synergies and collaborations among Whitehead Institute investigators and facilities and those at biomedical research organizations throughout the Boston, Massachusetts region, across the nation, and around the world. Leveraging the knowledge gained by the initiative’s investigations into the molecular mechanisms through which the X and Y chromosomes give rise to sex-specific differences in cells, tissues, and organs, the center will delve into the ways that those differences contribute to conditions of health and of disease in women.

It will bring together experts in sex chromosome biology and sex hormones, computational biology and cutting-edge analytics, and proteomics, epigenetics, and metabolomics — fostering the kinds of researcher collaborations never before undertaken and spurring new approaches to the many-variable problem inherent in sex differences research. The center will also pursue partnerships to translate and develop meaningful discoveries into clinical applications for diagnosing, preventing, and treating disease in women. Ultimately, Page envisions, center-driven collaborations and partnerships will include university or medical school-based and independent research organizations, pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers, and federal agencies.

Page, who will conclude his term as director in June, is also an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He has run a thriving research lab throughout his 35 years at Whitehead Institute, and is globally renowned for his groundbreaking research on sex chromosomes: His studies on the Y chromosome changed the way biomedical science views the function of sex chromosomes, and the work of his laboratory was cited twice in Science magazine’s “Top 10 Breakthroughs of the Year” — first for mapping a human chromosome and then for sequencing the human Y chromosome.

D’Arbeloff observes, “I have very concrete hopes for the center: I want it to help ensure that biomedical research reflects and benefits all of humanity — women and men, young and old. And I believe it is not hyperbole to say that David Page’s sex differences initiative truly has the potential to change the future of health care — for everyone.”