Professor Emeritus Woodie Flowers, innovator in design and engineering education, dies at 75

Woodie Flowers SM ’68, MEng ’71, PhD ’73, the Pappalardo Professor Emeritus of Mechanical Engineering, passed away on Oct. 11 at the age of 75. Flowers’ passion for design and his infectious kindness have impacted countless engineering students across the world.

Flowers was instrumental in shaping MIT’s hands-on approach to engineering design education, first developing teaching methods and learning opportunities that culminated in a design competition for class 2.70, now called 2.007 (Design and Manufacturing I). This annual MIT event, which has now been held for nearly five decades, has impacted generations of students and has been emulated at universities around the world. Flowers expanded this concept to high school and elementary school students, working to help found the world-wide FIRST Robotics Competition, which has introduced millions of children to science and engineering.

Born in 1943, Flowers was reared in Jena, Louisiana. He became interested in mechanical engineering and design at a young age thanks in large part to his mother and his father, who was a welder with a penchant for tinkering and building. Growing up, Flowers also expressed a love of nature and traveling. When he wasn’t working on cars or building rockets as a teenager, he was camping with his family in Louisiana or collecting butterflies. This interest in nature led to an award-winning science fair project on the impact the environment has on Lepidoptera. Flowers’ passion for both building and nature also helped him earn the rank of Eagle Scout.

Flowers received his bachelor’s degree in engineering from Louisiana Tech University in 1966. After graduating, he spent a summer as an engineering trainee for the Humble Oil Company before enrolling in MIT for graduate school. He received his master’s of science in mechanical engineering in 1968 and an engineer’s degree in 1971. Two years later he earned his doctoral degree under the supervision of the late Professor Robert Mann. For his thesis, Flowers designed a “man-interactive simulator system” for the development of prosthetics for above-knee amputees. He would continue to design above-knee prosthetics throughout his career.

As Flower’s academic career progressed, his wife Margaret acted as a partner in everything he did. Early in their marriage, when Flowers was just starting out at MIT, she worked to support their family financially. Later in life, she left her own career to partner with Flowers on his work in FIRST.

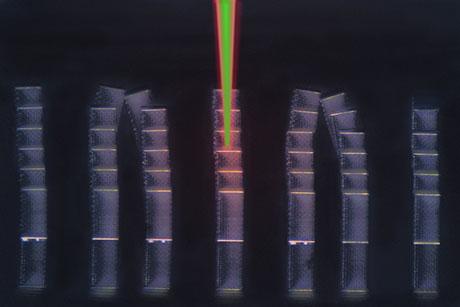

After earning his PhD, Flowers joined MIT’s faculty as assistant professor of mechanical engineering. Within his first year he was teaching what was then known as 2.70, now called 2.007. Under Flowers’ leadership, the class evolved into a hands-on experience for undergraduate students, culminating in a final robot competition.

“From the beginning 2.007/2.70 was about building a device to accomplish a task,” Flowers explained in a 2015 video. Students were given an assortment of materials to design and build their devices. In the 1970s these materials included tongue depressors and rubber bands, but over the years the competition has gone on to include 3D-printed parts and computer chips.

Despite the increased sophistication, according to Flowers the core of the course remained unchanged. “Some of the stuff that stayed the same is the wonderful way you compete like crazy but help each other out,” he said. Flowers would coin the phrase “gracious professionalism” to describe this idea of being kind and respecting and valuing others, even in the heat of competition.

PBS highlighted Flowers’ innovative educational approach to class 2.007 in a 1981 documentary “Discover: The World of Science.” The network continued to cover the 2.007 robotics competition throughout the 1980s, and nearly a decade later, Flowers hosted the popular PBS series “Scientific American Frontiers,” from 1990-1993. One of the program’s objectives was to get people interested in science and engineering. He was awarded a regional Emmy Award for his work on the series.

At the same time, Flowers helped develop a new program to inspire young people that built upon the competition he developed for 2.007. He collaborated with Dean Kamen, founder of FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), to develop a robotics competition for high school students. In 1992, the inaugural FIRST Robotics Competition was held, giving high school students from around the world an opportunity to design and build their own robots.

Over the past three decades, FIRST robotics has grown into a global movement serving 660,000 students from over 100 countries each year. It provides scholarship opportunities totaling over $80 million available to FIRST high school students. Flowers’ mantra of “gracious professionalism” remains at FIRST’s core. In 1996, William P. Murphy, Jr. founded the annual Woodie Flowers Award within FIRST to celebrate communication in engineering and design. The award “recognizes an individual who has done an outstanding job of motivation through communication while also challenging the students to be clear and succinct in recognizing the value of communication.”

While working on FIRST, Flowers continued to have impact on mechanical engineering education, its future directions, and engineers’ professional role in society, in addition to envisioning how the use of digital resources could enhance residential learning.

At MIT, he served as head for the systems and design division in the Department of Mechanical Engineering in the early 1990s and was named Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering in 1994. While Flowers retired in 2007, he remained an active member of the MIT community as professor emeritus up until his death.

Flowers mentored countless engineering students during his 35 years on the MIT faculty. He served as undergraduate and master’s thesis advisor for Megan Smith ’86, SM ’88, former chief technology officer of the United States, as well as doctoral advisor to David Wallace SM ’91, PhD ’95, Ely Sachs ’76, SM ’76, PhD ’83, and Alexander Slocum ’82, SM ’83, PhD ’85, all of whom are professors of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Flowers has had a lasting impact on the generations of mechanical engineering students he taught. From encouraging students to embrace ambiguity to pulling out a massive dictionary in the middle of class to help students find a precise word to articulate their point, his role in shaping students’ lives went far beyond the tenants of design and engineering. Many of his students who have gone on to be educators themselves have implemented his educational ethos in their own classrooms and labs.

Throughout his career, Flowers received numerous awards and accolades for his vast contributions to engineering education. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers honored him with both the Ruth and Joel Spira Outstanding Design Educator Award and the Edwin F. Church Medal. Flowers received the J.P. Den Hartog Distinguished Educator Award, was a MacVicar Fellow, and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering. He also served as a distinguished partner and a member of the President's Council at Olin College of Engineering.

Flowers is survived by his beloved wife Margaret Flowers of Weston, Massachusetts, his sister, Kay Wells of St. Augustine, Florida, his niece Catherine Calabria, also of St. Augustine, his nephew, David Morrison of Arlington, Virginia, as well as generations of grateful and adoring students.

Memorial donations to FIRST and memories of Flowers may be delivered via this website or mailed to FIRST c/o Director Dia Stolnitz, 200 Bedford Street, Manchester, New Hampshire, 03101.

This article will be updated with information about memorial services as it becomes available.