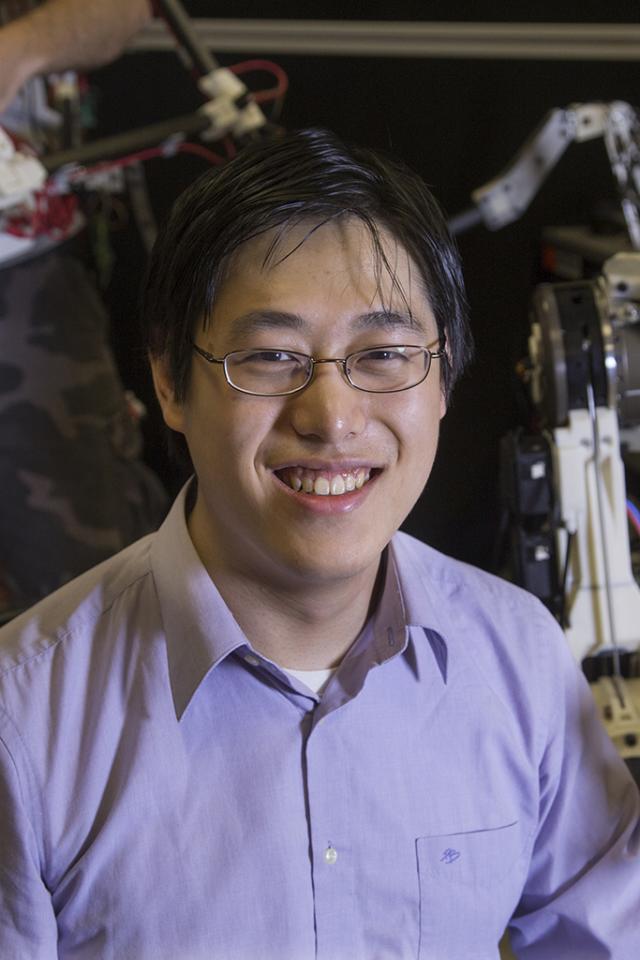

Jessica Xu

Everything is a canvas for senior Jessica Xu. A prolific artist, Xu has explored a number of media including pen and ink, colored pencil, and watercolor. In her time at MIT, she has expanded her horizon beyond traditional media — turning places on campus into works of art.

As a first-year student, Xu painted a mural in the tunnels beneath MIT’s campus through the Borderline Tunnel Project. Later on, she collaborated with UA Innovation to transform the "Banana Lounge” with student mural art. During this year’s Independent Activities Period, she co-led virtual “Chalk of the Day Workshops” to provide students with an artistic outlet during quarantine.

In addition to transforming everyday spaces into art, Xu draws inspiration from everyday spaces for her engineering work. When considering a redesign for TILT, a wheelchair attachment that allows users to navigate areas that aren’t wheelchair accessible, Xu was inspired by the design of traffic lights.

“That’s the artistic side coming in. I’m always looking around, finding connections between things and trying to draw inspiration from just about anywhere,” Xu says.

Upon coming to MIT, Xu was eager to focus on topics related to health and medical device design. She was particularly drawn to developing solutions for people to live more independently. When deciding what major to declare, she found her home in mechanical engineering.

“I landed on mechanical engineering in particular because I realized I’m much more energized working closely with end users to develop solutions,” she says. “Because of my background as an artist, I also tend to think in more physical or spatial terms, which made mechanical engineering a good fit.”

Xu enrolled in the flexible mechanical engineering Course 2A program with a concentration in medical devices and a humanities, arts, and social sciences concentration in history of architecture, art, and design. For her 2A concentration, she proposed a list of classes exploring a range of medical technologies from human augmentation to assistive technologies to designing medical implants.

“I really love the Course 2A flexibility in letting me focus on mechanical engineering while also diving into some of my other interests that aren’t regularly covered in the core engineering classes,” says Xu.

Fall of her sophomore year, Xu joined MIT’s Therapeutic Technology Design and Development Lab as a research assistant. Under the guidance of Ellen Roche, associate professor of mechanical engineering and W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering, Xu helped design a minimally invasive delivery system for a patch that could be placed on a beating heart and used to deliver drugs. More recently, she helped design a delivery tool for an implantable ventilator that actively moves a person’s diaphragm.

“Jessica is a methodical, creative, and talented engineer and an excellent communicator. She has been an absolute pleasure to work with on these two projects. Her mature understanding of the engineering design process enhanced the devices our team has been working on,” adds Roche.

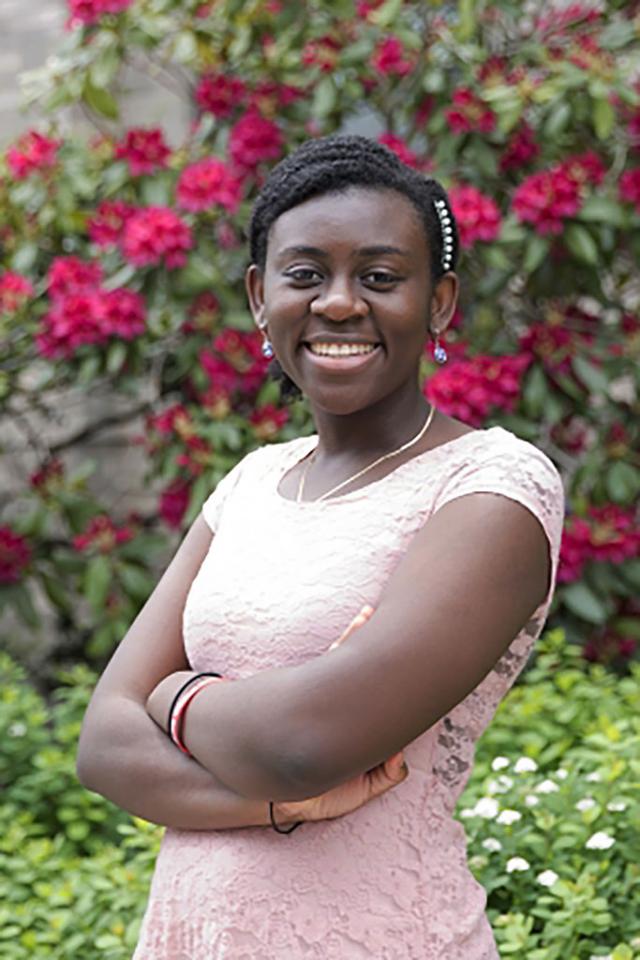

The same semester she started working with Roche on therapeutic devices, Xu joined fellow mechanical engineering student Smita Bhattacharjee working on TILT, which began in class EC.720 (D-Lab: Design). The project hopes to address the lack of wheelchair accessibility in developing regions, particularly in India.

“This is not just a technical problem, it’s a huge social problem. Wheelchair users in these regions often can’t easily exit their home, go get an education, go to work, or just engage with their communities,” Xu says.

TILT offers a solution for the lack of wheelchair accessibility. A pair of ski-like objects attaches to the wheelchair, enabling someone to easily help wheelchair users glide up or down stairs. This simple design makes TILT easy to use in regions with limited resources, especially compared to more expensive solutions such as robotic stair climbing wheelchairs.

“The effort began as a collaboration between MIT and Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) students with the encouragement of one the D-Lab Design instructors,” adds Sorin Grama, a lecturer at MIT D-Lab. “It was a great example of an international collaboration to understand and solve a pressing need in an emerging market, a core tenet of D-Lab.”

Inspired by how traffic lights are hung, Xu made a critical redesign of TILT’s attachment mechanism. With the design optimized, the pair was joined by another mechanical engineering student, Nisal Ovitagala, and they began to explore how to best ramp up manufacturing at scale and develop a business model. They sought help and funding from programs including MIT Sandbox Innovation Fund Program and the Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship at MIT to improve their entrepreneurial skills.

This assistance paid off as the TILT team was awarded a $10,000 juried grant at the IDEAS Social Innovation Challenge in May 2020.

Bhattacharjee, Xu, and Ovitagala have been continuing work on TILT throughout their senior year. Most recently, they have worked on further physical prototyping and design ideation with the user experience in mind. They hope to start field testing with wheelchair users in India once travel becomes safe.

Xu has also explored her passion for democratizing health-care innovation through her involvement in MIT Hacking Medicine. Most recently, she was the event co-lead for Building for Digital Health 2021, which featured a tech talk series and a hackathon organized in partnership with Google Cloud.

Xu sees parallels between her work on medical devices, including TILT, and how she views art.

“When we look at art, we see an idea that’s portrayed through the lens of the artists, the patron, the culture at large. We always need to question what or who is left out, either consciously or unconsciously. What are we not seeing?” Xu says. “It’s the same with engineering, especially with medical devices and projects like TILT. When I’m working on addressing problems for people that I don't have the lived experience of, I always need to question: What assumptions do I have? What blind spots do I have? What am I not seeing?”

After graduating this spring, Xu plans to pursue a master’s degree to build upon the work she has done at MIT in preparing for a career in the medical device industry. Whatever the future holds, she plans on combining her twin passions of engineering and art to solve problems that improve the lives of others.