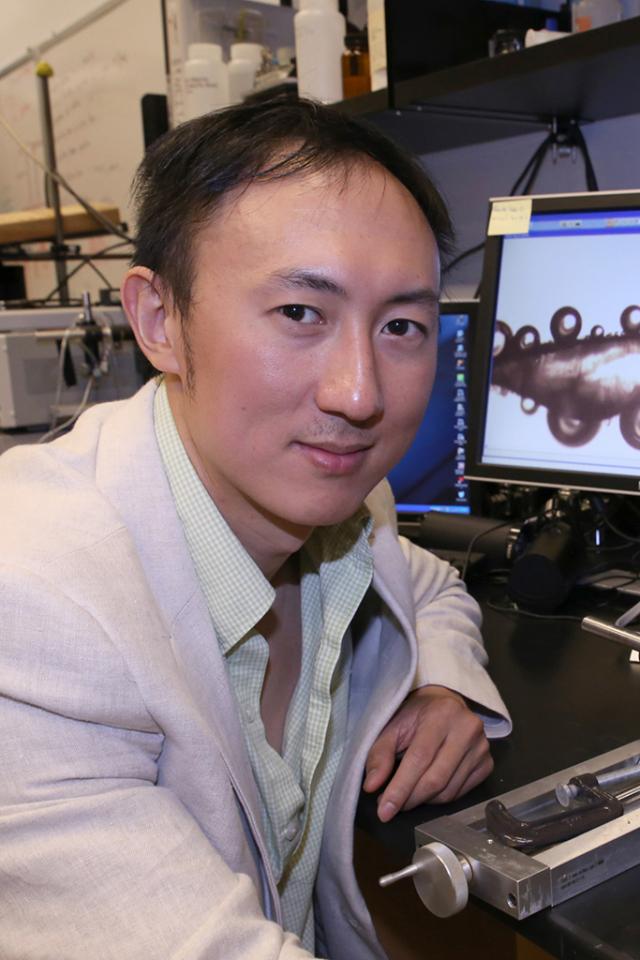

Peter Lehner

Peter Lehner had always been interested in mechanics, even as a teenager. He loved rebuilding old cars and wanted to become an aircraft engineer after college.

“I knew a man named Mr. Cotchett who was a mechanical engineer during the Depression,” explains Lehner. “He was involved in the textile industry, which the family company Leigh Fibers was in, and that’s how I met him. He ran a machine shop too, and eventually took me on as an apprentice. He understood mechanics and how to control fibers better than anyone else I knew.”

Lehner was 16, and his time as an apprentice in Cotchett’s machine shop solidified his interest in mechanical engineering. A few years later, he came to MIT on the GI Bill and majored in mechanical engineering. Back then, says Lehner, a lot of students were wearing uniforms, and there were only two women in his class.

In 1948 and 1949, Lehner was a member of the MIT Crew team. In ’48, his team beat everyone they rowed against and was asked by the Olympic Committee to try out for the Olympics. They rowed in Princeton, NJ, against a team they had beaten before, but this time, they lost out by six inches. “That was definitely a highlight of my time at MIT,” he recalls, “topped only by meeting my wife Mary, without whom I might not have made it through.”

After graduation, Lehner started a plastics company with his mentor, Cotchett. According to him, they were the first company outside of Dupont to mold Fm-10,001, but they eventually went out of business. “I’d say it was a very good thing actually,” he says, “because going bust makes you realize that the bottom line really does count, and that’s something I think a lot of young engineers could stick in the back of their brain.”

Soon after, Lehner went off to work at a shipyard, but when Leigh Fibers started having trouble with some of its machines, he focused his attention on the place he least expected: the textile industry.

At Leigh, Lehner not only fixed the machines but also significantly increased their efficiency and, ultimately, the company’s throughput and product range as well. But his real value wasn’t revealed until he started helping customers solve their mechanical engineering and fiber problems too. Lehner was able to see new ideas and develop new solutions that others had not; he worked in this way to the point where, according to him, he didn’t have to find a single customer – they all came to him with a problem and, once he solved it for them, became a customer.

“The fact that I knew how machines and textile fibers worked together was the best thing I had. Once I helped companies with that, I could sell them my product,” he says.

Today, Peter is still active in the textile waste business at Leigh Fibers, which has since transferred its focus to carpets.

“Right now, our biggest operational challenge is trying to find a way to use the carpet carcass. That’s our biggest worry because 70% of every carpet is carcass. Nobody knows what the value of the leftover is yet, but we’ll find it.”